We don't know what we don't know

Sometimes it's important to remind ourselves that we don't know what we don't know!

I recently began to spend more effort considering and emphasizing what pieces might be missing from a particular engineering puzzle. Like many engineers, I rely heavily on mental models when tackling technical problems. The problem is, these mental models are seldom complete, with gaps or assumptions, which leads to mistakes or discounting approaches to a question we didn't know to consider.

Let's spend some time considering what it means not to know what we don't know and how we can remind ourselves of some of our own biases.

My first experience with WDKWWDK

For me, this realization first came during a meeting.

We were trying to tackle a specific security challenge that required selecting a cryptographic protocol with particular properties. I was in the position to make the recommendations, which came down to Noise based on some industry experts' suggestions.

The problem we had is we weren't able to locate an implementation of the protocol for our embedded CPU. While I was evolving into a security lead for the team with a better than average understanding of security principles, I was utterly ill-prepared to write a crypto implementation that would pass any scrutiny.

However, with the most knowledge, the team asked me to develop the implementation.

I objected, indicating that writing a cryptographic implementation is detailed work, and it's challenging to be sure that the implementation is correct.

The team countered, saying that it must be correct if the implementation can communicate with another library (on a known CPU architecture).

The problem is it's possible to write a compatible protocol implementation, that has significant security problems. Re-using nonces or timing attacks could ruin our day, and we'd easily miss out on the security properties we desired.

The team countered again, indicating that if I knew about problems like nonce re-use or timing attacks, that I should avoid those problems.

Any problem I can describe in theory should be a problem I can avoid.

Eventually, I had to figure out to approach this engineering conversation as an admission, I don't know what I don't know, so I'm ill-prepared to solve problems I don't even know to avoid.

Not only did I need to admit what I didn't know, but as a team, we had to admit combined that we didn't know what we didn't know. In many scenarios, we may be able to get away with this, but here, a failure meant we failed to deliver on our security promises to our customers.

Is this the Dunning-Kruger effect?

For those who aren't familiar, a simplified version of the Dunning-Kruger effect states that a cognitive bias exists where individuals with limited knowledge or competence in a given intellectual domain greatly overestimate their expertise or skill in that domain. And that those with a great deal of expertise tend to underestimate their results.

This cognitive bias is fascinating and may explain some of the "solutions" or "projects" we see that claim perfect security while not holding up to basic scrutiny.

While the Dunning-Kruger effect may apply here, we often forget that this cognitive bias only means that people scoring in the 12th percentile had ranked themselves in the 62nd percentile. But those in the 90th percentile had self-assessed to be within the ~75th percentile.

Dunning-Kruger effect on research gate for more information

Dunning-Kruger effect on research gate for more information

With this in mind, on average, individuals without much exposure do not rank themselves as experts in an area they don't know.

We can still draw an important lesson here; that we need to be aware of and careful of our biases, whether it be the Dunning-Kruger effect or something else.

Unconscious Fear

As engineers, I think we get used to analyzing complex problems and coming back with answers. Especially those of us who are known for digging in and finding the solutions.

When given a task, there may also be a particular fear associated with not having the answer. If your leadership or team members expect you are an expert in a domain and are assigned a problem, it feels like a failure to return without the full solution.

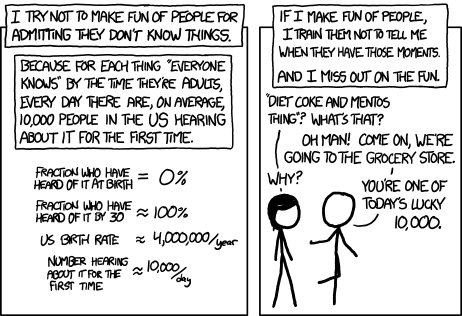

For me, it's even come to the point where others have tried shame me in front of my peers for not knowing some technical detail off hand. This behaviour creates perverse incentives that it's better to stick with an assumption than admit we don't know something. I know I've unconciously affected others in this same way, which is one of my regrets.

A large part of this is realizing it's not a failure to admit that we have missing knowledge. We may not remember some details or have more research to do. Maybe there is no action required. The failure is to proceed without identifying the risk of the missing information. Whether an expert or not, there are always going to be missing details. When working in security, the missed detail could be the difference between high and abysmal security. In other domains, the risks may be much different.

Knowing the risks of missing information allows us to choose whether to accept those risks.

How do I apply this?

I think it's as simple as stating, "We don't know what we don't know" in a conversation, or typing WDKWWDK into a document or chat session. And ensuring our teams and leaders don't allow a stigma to exist around not knowing some details.

I'm not the first to use this acronym, but I also don't believe we use it enough.

This statement of fact, acts as a reminder, that we should step back and consider how our biases may impact a particular decision or design and to identify what information may be missing.

We can then consider:

- What we know

- What we know we don't know

- If there is anything we don't know what we don't know that needs exploration

And decide on the risks of proceeding with missing information, cognizant that there will always be missing information.

Summary

Before committing to an approach to an engineering problem, remind yourself or the team that there are likely missing details that may affect the outcome. How to proceed largely depends on the risks involved, topics like security have different risks than the CI/CD pipeline.

And we need to remind ourselves and our peers to avoid the stigmas and biases introduced by admitting we don't know things. Being an expert in a domain like security, doesn't mean memorization of every algorithm, every protocol, or approach.